This is a favorite piece from my archives, originally published in the New York Times Book Review back in 1994. This wordless children’s book went on to win a Caldecott. Its nice to know that my review may have helped bring it the attention and honor it deserved.

This is a favorite piece from my archives, originally published in the New York Times Book Review back in 1994. This wordless children’s book went on to win a Caldecott. Its nice to know that my review may have helped bring it the attention and honor it deserved.

Time Flies

Written and illustrated by Eric Rohmann. Unpaged. New York: Crown Publishers. $15. (Ages 4 to 7)

AS far as children’s dinosaur books go, I am one bored-asaurus. The last thing I’m interested in is having another preternaturally bright tyke give me the lowdown on another prehistorically cool critter. I don’t want to have to memorize any more multisyllabic creature names and corresponding eating habits in order to keep up with the 8-year-old Joneses.

In “Jurassic Park” we grown-ups were asked to consider the awesome power of dinosaur chromosomes trapped in ancient amber. Many dinosaur books for youngsters take a similarly powerful source — the imagination of children — and lock it up in literalism. Sure, dinosaurs are a great way to get youngsters interested in the natural sciences, but it’s sometimes sad to see them emerge from their reading with little more than memorized lists of traits and behaviors.

Well, grab hold of your trembling water glasses, moms and dads! A new kind of dinosaur book is stomping onto the scene, and it’s going to make a lot of people very happy. Eric Rohmann’s “Time Flies” is a work of informed imagination and masterly storytelling unobtrusively underpinned by good science.

Told through a sequence of beautifully rendered illustrations by Mr. Rohmann, “Time Flies” is an entirely absorbing narrative made all the richer by its wordlessness. Youngsters will want to talk to their adult friends about the book in terms of its excitement, surprise and suspense, and they won’t be held back by a fixation on terminology. So often they come away from a dinosaur book saying “ichthyosaur”; this one will make them say “wow!”

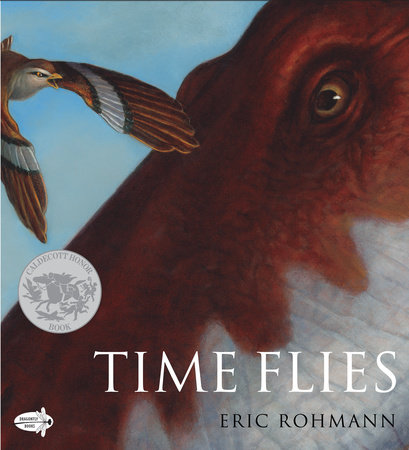

Mr. Rohmann’s tale takes place on a stormy evening. It is dusk. Lightning rips the murky sky, and you can almost hear it crackle. A lone bird flees a barren tree, flying toward an abandoned building and leaving a quiet scattering of dull grayish-brown feathers in the wake of its flight. Carried on the wind, the bird swoops through an open window, discovering the building to be an ominously Gothic old museum, complete with bony-winged gargoyles menacingly mimicking our avian hero. And on display in the museum’s gargantuan grand hall? A frightful assembly of dinosaur skeletons, casting threatening shadows on the walls.

As the bird explores this dusty boneyard, darting inside the hollow rib cages and balancing on the petrified teeth of long-dead beasts, something strange begins to happen. Flesh rematerializes on bone, the dark museum floor becomes a pastel-hued mountain range and, instead of playfully zipping between fossilized jaws, the bird finds itself suddenly skittering above the all-too-meaty tongue of a live dinosaur.

The paintings have both dynamism and direction. The viewer’s eye follows the curve of a wingspan to the descent of a massive tail and back up again on the graceful neck of a monster. We are tempted to loop and linger, but then the piercing energy of a creature’s beak tells us to turn the page — quickly!

There is a sense of scale here rarely pointed up as clearly in nonfiction children’s books about dinosaurs. It’s one thing to read that T. rex is as long as a dozen cars, but there’s much more visceral impact when Mr. Rohmann’s images make you fear that if that big guy blinks, the bird might well get stuck under his eyelid.

His cunningly composed two-page spreads are rich with echoes and ambiguities that will provide the stuff of many a thoughtful conversation between readers of different ages. In one sense, “Time Flies” is an old-fashioned scary yarn in which skeletons come to life. But it can also be interpreted as a bird making subconscious connections with its reptilian ancestors (look at Mr. Rohmann’s pointed parallels between the creatures’ bone structures). Or — most interestingly, I think — the bird can be understood as a projected surrogate for the imagination of a child set free amid the dry facts of history and science.