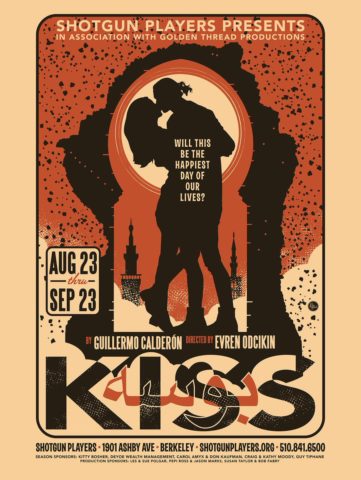

Originally published in the Bay Area Reporter

On the first page of the program for Shotgun Players’ production of Guillermo Calderón’s “Kiss,” “A Note from the Director” is subtitled, “Spoiler Alert: Please read after the show!”

On the first page of the program for Shotgun Players’ production of Guillermo Calderón’s “Kiss,” “A Note from the Director” is subtitled, “Spoiler Alert: Please read after the show!”

Meta-Spoiler Alert: If a director, in this case Evren Odcikin, believes that a plot twist is the most noteworthy aspect of his play, what’s about to be spoiled is an audience’s evening.

Spoiler Alert: The primary plot twist in “Kiss”‘ three-sectioned script, performed in an intermissionless 90-minute eternity, is that the first of those sections, an overwrought melodrama, is revealed to be a play within the play. Thank goodness, because it’s laughably awful, a Damascus-set contemporary love triangle that somehow avoids any mention of Syria’s ongoing war and suffering.

What a relief for the mystified Shotgun audience when, about 40 minutes in, the soap episode concludes with the four leads taking a faux curtain call, then suddenly switching from their melodrama characters to their second roles: playing the actors who performed in the melodrama, now ready to engage their audience in a post-play discussion. This sublimely executed gimmick is by far the production’s most effective mind-meld of playwright, director and cast. There were audible gasps of surprise in the theater on the night I attended.

The well-meaning Actors, led by Laura (Elissa Beth Stebbins, deliciously over-earnest), explain that they originally discovered the script of their play online, posted by its exiled Syrian playwright, Amira, who has recently been located in a Lebanese refugee camp. Now, for the first time ever – suspend disbelief! – they are about to meet Amira, via Skype, to publicly discuss her play along with the audience that’s just seen their performance. The ensuing scene is handled with acute verisimilitude, from the Actors fumbling with a computer projector, to a temperamentally staticky livestream, to the palpable frustration of Amira (Rasha Mohamed) speaking through a translator.

She quickly realizes and points out that these sensitive Western thespians have completely misinterpreted and mistranslated her play, deaf to its cultural context. Written as sorrowful, tragic realism, it’s been turned to buffoonery by arrogant would-be do-gooders.

This scene is tight and impactful. The audience squirms, feeling the Actors’ profound embarrassment. It’s a dramatically powerful, well-crafted demonstration of ill-informed assumptions undermining good intentions. Despite an overlong opening gambit, playwright Calderón has delivered, clearly and cleverly.

But Calderón immediately gilds the lily: The troupe’s distraught correspondent goes on to explain that she is actually not the Playwright (who has been killed), but her bereaved sister. We see her projected on the wall crying, “I am not Amira. I am not Amira.” We get it. The lives of Middle Eastern refugees and those of comfortable Westerners aren’t reflective (nudge, nudge) of each other.

“Kiss” is already a convoluted play. Why add a superfluous character death for no clear reason beyond wedging fanciful wordplay into a scene that otherwise draws its power from its realism?

Turns out, Calderón’s just getting started. We’re on to Part 3, where nothing makes sense. While rightly mortified, the Actors don’t apologize to Amira’s sister, or to their audience. After the conference call abruptly comes to an end, they huddle up in a private chat, then jump into a do-over. Slipping back into character mode, they attempt to perform the same script, but with the tone and nuances its playwright intended.

Of course, in a single phone call, they’ve had but the slightest glimpse of Amira’s reality. So they’re not really making reasonable adjustments, just another set of mistakes. And this set can’t be written off as daft naiveté; it’s unthinking, guilt-wrenched flailing. Which is not enjoyable to watch.

Calderón seems to realize that it’s unreasonable to force audiences to sit through the full length of this misguided attempt at redemption. But his solution throws things into further disarray: As the cast performs a stylized, fast-forward abridgement of the first act, the play’s entire meta-conceit of audience-as-character, experiencing events in real time with the Actors, is destroyed, and Calderón’s script begins to contort into nonsense.

The Actors solicit a few audience volunteers to join them on stage to play the role of a smaller audience, breaking rules of both physics and logic. The entire play now feels trapped in a corner of Calderón’s making. Having whipped up a frantic dynamo energy, it literally explodes.

Booms. Flashes. Gusts of smoke. Amira/Not Amira glides sepulchrally forward onto the Actors’ cozy living room set. Dimensions have collided! Time and space have deformed! The horror of war is incomprehensible! Art can never replicate life!

Now you get to read “A Note from the Director.” Odcikin’s commentary doesn’t actually give much away at all. You could read it ahead of time and still be surprised. Both by the big plot twist, and the big mess that follows.