Adam Ashraf Elsayigh is having a moment. It’s an exciting time for him. It’s also a bit unsettling.

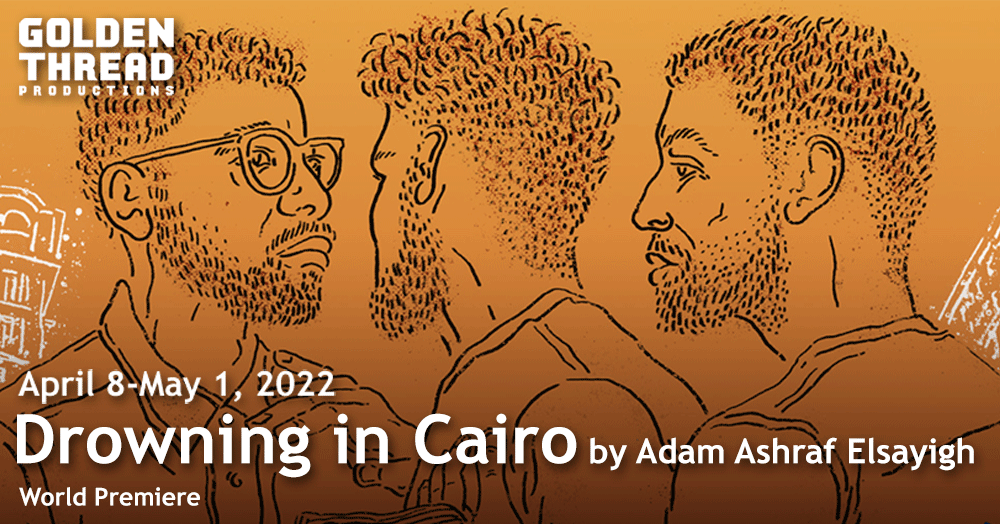

The Egyptian-born, New York-based writer will arrive in San Francisco this week for the opening of Golden Thread Productions’ world premiere production of his play, Drowning In Cairo, which is about — Well, here’s where it gets complicated.

Golden Thread’s publicity copy, written by director Sahar Assaf, for whom Elsayigh has nothing but praise, sketches the show as follows: “It is May 2001 in Cairo…on the Queen Boat, a gay nightclub docked on the Nile. When an unexpected police raid results in the arrest and public humiliation of the attendees, the lives of these young men are altered forever.”

The Queen Boat raid, an actual event that drew worldwide attention, became a watershed moment for queer visibility in Egypt. But before speaking with me last week, the thoughtful, self-conscious 25-year-old Elsayigh emailed his playwright’s note, which will also be included in programs distributed at the theater.

Elsayigh writes “I will never forget when…after a reading of Drowning In Cairo in New York an audience member asked me what he could do to ‘help gays in Egypt”…Another congratulated me for writing this play because it was ‘so important.’”

In his note, rather than perceiving these comments as cause for pride in his work and its impact, Elsayigh characterizes them as “a testament to the limitations of ‘representation politics.’ Queer Egyptians were represented that night but it didn’t mean a thing because the audience who came to see it were only there because it was ‘important’, because of what it said about them to be the audience of ‘a queer, Arab play.’ They projected their assumptions about the big bad Middle East onto the play and saw what they wanted to see in it…They came to see what would confirm their bias, their superiority.”

There may well be some audience members who attended that reading—and who will attend the Golden Thread production—for purposes of self-beknightment or virtue signalling.

But they wouldn’t be the only ones projecting assumptions.

Should white ticket buyers for Slave Play, straight audience members at The Boys in the Band and white, straight audience members at Drowning In Cairo be reflexively considered malintentioned or worthy of suspicion?

Elsayigh, who has degrees in theater and playwriting from New York University’s Abu Dhabi campus and the City University of New York (both earned through full merit scholarships), has been thoroughly immersed in critical theory. But as a young queer person, an Arab-American and an emerging artist, he now has to wrestle with the real world complexities of identity politics, self-consciousness and self-confidence.

“I’ve been in situations,” he confides during our interview, “where I’ve met with a producer or an artistic director and its been clear that they’re only interested in my work because they’ve been called out for not having produced an Arab playwright or a gay playwright.”

“Look,” he says, “If people come because they want to hear from a queer Egyptian voice, that’s cool. I’m not offended by that. But when you actually come through the door, try not to come with assumptions about what I have to say or how I’m trying to challenge you.”

To the sensitive, thoughtful Elsayigh, one of the hazards in a writer having their work assumed to be representational is the potential self-censorship that ensues. “I want to write Muslim characters and trans characters and disabled characters who do shitty things and be assholes—and are also like people we love.”

Drowning In Cairo follows its three characters over the course of two decades, and they all do shitty things. Only two of 11 scenes take place in 2001, the year of the Queen’s Boat raid. “The fact that they were on that boat reflects who they were beforehand,” says Elsayigh, “and it affects how they move through the world afterwards.”

Its surely more than a coincidence that the aftermath of the raid, which occurred when Elsayigh was still a toddler, has generated debates about the Catch-22 of identity and visibility among queer people in the Arab world.

“I’ve heard a number of people refer to the Queen’s Boat as the Stonewall of Egypt,” says Elsayigh. “I have mixed feelings about that: Stonewall started a move toward significant policy change and social reform in the U.S; The Queen’s Boat raid actually did the opposite.”

“It wasn’t the first time a gay person was arrested in Egypt, and of course there had always been men who were having sex with other men. But this was the first time it was made so public and was transformed into a government propaganda item, promoted to straight Egyptians in a way that was vilifying and condemning. Since then, there’s been consistent, active raiding and terrorizing of queer identities and queer spaces.”

“In some ways,” reflects Elsayigh, surely aware of the irony in regard to his rising reputation as a playwright, “Becoming visible takes away some of your sense of being in control.”