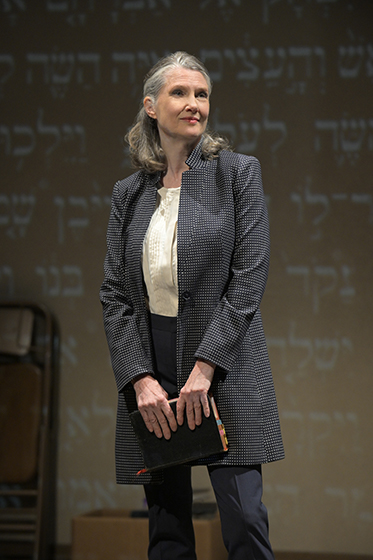

Miriam, the sharp-witted atheist academic played by Annette O’Toole in “The Good Book,” now at the Berkeley Rep, is the kind of professor whose bravura makes a lecture hall come alive—passionate, funny, insightful, provocative. She’s the teacher whose class would be worth taking, regardless of the subject, someone who can make Russian history or modern architecture or Victorian textiles become a lens through which the whole world can be seen afresh.

And “The Good Book” by Denis O’Hare and Lisa Peterson has a lively mix of content worthy of such an engaged delivery: Facts, hypotheses, anecdotes, jokes and challenging questions. The subject is the bible, Old Testament and New, which happens to be a lens through which many already see the world (And a topic many others would normally be inclined to steer clear of).

While Miriam’s lectures on the origins and history of the bible don’t make up the bulk of the “The Good Book”, they establish an overarching tone for the evening: Things move swiftly and build in collage. Brief didactic passages are thoughtfully layered with snippets of Miriam’s personal life; the story of Connor (Keith Nobbs), a young gay man who grew up in thrall of Catholicism; bible scenes; and scenes of bible scenes being written. Or, as Miriam would insist: “Not written. Assembled!”

Among the major tenets O’Hare and Peterson share via Miriam is the notion that the bible is by no means the word of God—or of any single author Instead, they argue, it too is a collage, a gathering of chronicles and imaginings and opinions that came together over hundreds of years. It’s a still evolving, perpetually changing work.

That transfixing unfixedness is reflected in Rachel Hauck’s flexible canvas of a set and Alexander V. Nichols’ handsome projections, which elegantly move the audience across continents and centuries. And it’s embodied by the shapeshifting five actor ensemble that complements O’Toole and Nobbs, nimbly moving between dozens of roles from medieval monks to wandering Jews to a journalist from “The New Yorker.” Nobbs’ performance as Connor is remarkable. While we meet the character in his twenties, we spend most of our time with him as a youngster. Through rapid diction and subtly awkward postures, Nobbs gives us an utterly believable tween believer without a single comedic overstep.

Though the playwrights and their protagonists don’t believe in Creation, they’re smitten with creative process. “The Good Book” argues for the appreciation of the bible as one of humankind’s greatest collaborative artworks. Many non-religious theatergoers will consider this a fresh and even generous perspective. Religiously observant audience members may feel unaddressed though; for all its vivacious, Stoppard-worthy intellect, the play largely sticks to the literary bible, sidestepping substantial engagement with the notion of religious faith. When Miriam and her partner of many years break up after he admits—as if its a crime—that he believes in a higher power, we see the pain and confusion of her personal loss but no prospect of subsequent spiritual awakening. That said, “The Good Book” is fundamentally not for fundamentalists. It’s an evening of whiz-bang bible study for the curious heathen.