The closing scene of “Dear Evan Hansen” brings us to a clearing. The characters assemble before a bright blue scrim of open sky. The band, on a platform above the stage, is crisply silhouetted. The singing is hushed but strong. The fading final chord of Benj Pasek and Justin Paul’s truly beautiful score offers a simultaneous sense of resolution and opportunity.

The closing scene of “Dear Evan Hansen” brings us to a clearing. The characters assemble before a bright blue scrim of open sky. The band, on a platform above the stage, is crisply silhouetted. The singing is hushed but strong. The fading final chord of Benj Pasek and Justin Paul’s truly beautiful score offers a simultaneous sense of resolution and opportunity.

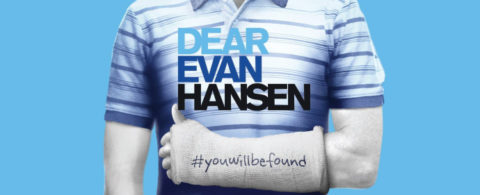

Until then, the stage of the Curran Theater, the latest stop on this Broadway phenomenon’s first national tour, has been an emotional shadowland. Steven Levenson’s smartly knotted plot has 16-year-old, anxiety-disordered Evan spinning a web of deception (self- and otherwise) about his friendship with Connor Murphy, a classmate who has taken his own life. As one web leads to another, the online amplification of Evan’s assertions entangles a sizable community.

The show’s design team (David Korins, scenery; Peter Nigrini, projections; Japhy Weideman, lighting) boldly conjures a dark vision of contemporary suburbia in which the characters and their domestic comforts — bedroom sets, sofas, a hobbyist’s workbench — are flotsam in a churning sea of social media feeds and psychic pain. Remarkably, this visual approach, along with a story that delves into depression, divorce, and suicide, doesn’t pull “Dear Evan Hansen” or its audience under. While setting and story don’t fully “step into the sun,” as one lyric puts it, until the show’s final moments, Pasek and Paul stitch threads of light through darkness from the outset. Hope flows through their urgent, plangent songs, and the audience wants to follow it.

“Anybody Have a Map?” is about being lost but not giving up. “Waving Through a Window” describes alienation while keeping the possibility of belonging in sight. “You Will Be Found” offers acknowledgement to the overlooked. And “So Big/So Small” ingeniously alchemizes loss and despair into security and promise.

With the exception of one comic number, “Sincerely, Me” (genuinely funny), there isn’t a tune in this show that’s straight-up upbeat. But the mid-tempo songs’ guitar- and string-inflected arrangements have an addictive bittersweetness, and Paul’s fragmented melodic structures twist and turn in ways that keep one engaged. Each song shines on its own, but their coherence as a whole is a greater accomplishment.

The touring cast is as strong as the book and music. “Dear Evan Hansen” rose to fame between 2015-17, as did Ben Platt, who originated the title role. But Ben Levi Ross, playing Evan on tour following an understudy stint on Broadway, has a distinct advantage in his lack of celebrity status. Because we’re not watching a familiar star perform the part, our connection to Evan feels unmediated. Every awkward stammer, facial tic and flail of Ross’ gangly limbs feels utterly, sometimes uncomfortably real. At times I found myself squirming in my seat in somatic sympathy. Rather than make you miss Ben Platt, Ross brings you closer to Evan Hansen.

The touring cast is as strong as the book and music. “Dear Evan Hansen” rose to fame between 2015-17, as did Ben Platt, who originated the title role. But Ben Levi Ross, playing Evan on tour following an understudy stint on Broadway, has a distinct advantage in his lack of celebrity status. Because we’re not watching a familiar star perform the part, our connection to Evan feels unmediated. Every awkward stammer, facial tic and flail of Ross’ gangly limbs feels utterly, sometimes uncomfortably real. At times I found myself squirming in my seat in somatic sympathy. Rather than make you miss Ben Platt, Ross brings you closer to Evan Hansen.

Jessica Phillips delivers a deeply nuanced Heidi Hansen, Evan’s hardworking single mother, in whom pride and frustration do battle on a daily basis. She’s such a well-wrought character that when Evan lashes out at her, you want to slap the kid who’s been winning you over. Phillips’ stunning performance of “So Big/So Small” makes you look back at the show from another perspective.

Jared Goldsmith gives surprising texture to the role of Evan’s “family friend” Jared Kleinman. It’s a part that could be played solely for comic relief , but he deepens it with a mean streak and ingrown loneliness. Phoebe Koyabe brings out subtle shades of motivation in Alana, the awkward, overachieving schoolmate who turns grieving Connor into a social media phenomenon. As Zoe, the dead boy’s sister and Evan’s longtime crush, Maggie McKenna gives us a compelling tangle of sorrow, anger and an impulse for caretaking.

Director Michael Greif brings the same psychological sensitivity to “Dear Evan Hansen” that marked his staging of “Next to Normal,” another contemporary musical that grappled with family grief and mental illness. Here, as in that show, he elicits heartfelt and deeply integrated ensemble performances.

Suicide, anxiety and depression are not the traditional stuff of musical theater. But Greif, Pasek and Paul seem to understand music’s palliative power. Not only can its presence make it easier for us to reflect on difficult topics, music can also, however fleetingly, lessen our pain. “Dear Evan Hansen” offers no cure for the social ills it surveys. But it sings as it searches. And it brings us to a moment of clarity and hope.