By Jim Gladstone

In Elise Primavera’s color-drenched pastiche of a Yuletide tale, the first hue that really strikes you is not a traditionalist’s Christmas red or green but the bright yellow of taxi traffic.

Honk if you love Manhattan in December. Otherwise, take this first flash of yellow as a caution light.

Even if children’s books aren’t on your shopping list this season, you may have already run across the adventures of Primavera’s ”Auntie Claus.” Dioramas based on the book’s illustrations once filled the holiday windows at Saks Fifth Avenue—an entirely appropriate showcase.

”Auntie Claus” is packed with all the simultaneously wonderful and troublesome elements of a contemporary uptown holiday season — great gobs of visual stimulation, spectacular displays of material wealth, precocious children who have it all and a light overlay of moral sentiment that doesn’t exactly resonate with sincerity amid the exuberant excess.

Toward the end of ”Auntie Claus,” the story’s young heroine, Sophie Kringle, announces that she has come to understand that ”it is far better to give than it is to receive.” She does this standing amid the candelabra, gilded furnishings and small forest of ornamented trees that decorate her family’s penthouse apartment. Tiny Tim territory this is not.

High-mindedness aside, if you’re the type of parent who can allow your kids to indulge in an occasional candy cane pigout without fretting over nutrition, ”Auntie Claus” is well worth a splurge. Primavera serves up visual bonbons that will make your eyeteeth ache: a gargantuan Santa head bobs through the night sky like a float broken free from the Macy’s parade; the North Pole is studded with curvaceous, colorful minarets; a giant snow dome serves as a surveillance device; and Santa’s elves wear eccentric two-pronged headpieces that owe a clear aesthetic debt to the furniture designs of Philippe Starck.

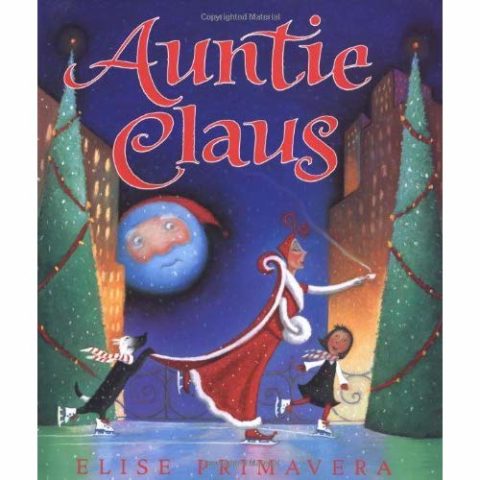

Young Sophie’s Auntie Claus herself is like an Erte figure in red-and-white fur, with a tasteful whirl of feathers atop her pointed Art Deco hood. She emanates genteel flamboyance, and has a nose so surgically sharpened you can imagine getting a paper cut from touching it. If you read this book aloud, it will only be fitting to pronounce the grande dame’s name as ”Ahntie Claus.” The story is simple and none too surprising. Spoiled little Sophie stows away in a steamer trunk and learns that her glamorous, elusive aunt — She’s so mysterioso!” — is the ermine-trimmed brains behind Santa’s whole Arctic gift distribution operation. And thanks to Auntie’s subtle intervention, she decides to be generous at Christmas and stop being such a brat to her baby brother, Chris. (Given Sophie’s ridiculously pampered milieu, most adult readers will be skeptical about the possibilities for her attitude adjustment lasting much beyond New Year’s Eve.)

Primavera’s gouache-and-pastel illustrations, loosely rendered, brim with fantastic energy, particularly in a pair of delightfully disorienting vertical spreads that require the reader to flip the book around on his lap to peruse them from top to bottom. One of these, in which Auntie Claus blasts off to the North Pole from Manhattan in a gilded flying elevator, seems rather baldly derived from Roald Dahl’s ”Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.” But Primavera borrows from the best, and this image delivers a jolt of delight, as do her Dr. Seuss-like elf abodes, a Lane Smith-style close-up of bawling baby Chris, and a monumental klieg-lighted snowman almost shamelessly reminiscent of William Joyce’s 1993 holiday offering, ”Santa Calls.”

In a book that’s somewhat overstuffed with calculated pleasures, Primavera does work in one utterly charming motif that laces a quiet, quirky humor into the unsubtle humongousness of the book’s overall high-kicking Rockette approach. From the very first time we meet Auntie Claus, she is accompanied by two fastidious canine attendants. These black-and-white mutts with jingle-bell collars carry the train of Auntie’s cape, cheerfully schlep her luggage and accompany her to a North Pole award ceremony. But clearly they are more than mere flunkies. In a single illustration, wisely not referred to in the text, they appear to possess unusual powers. When Auntie Claus’s dogs appear to serve themselves Christmas cookies and tea by exercising telekinetic powers, Sophie looks on in shock, and a touch of real magic cuts through the more bombastic entertainment.

Originally published in The New York Times Book Review