Guy Branum is the zaftig Sontag of comedy.

Guy Branum is the zaftig Sontag of comedy.

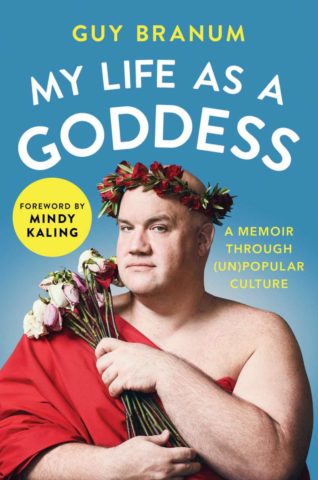

His brainy magpie’s nest of a book, My Life As A Goddess: A Memoir Through Unpopular Culture, has just been released, and it presents a more prickly, philosophical and intellectual point-of-view than we usually expect from comedians.

“A lot of people don’t know what to make of the book,” says the stand-up comic, television writer (The Mindy Project, Joan Rivers’ Fashion Police) and, now, author.

“They assume it’s going to be one of those comedian’s books that has their old stage material written down along with some stories from their childhood and that sort of stuff.”

While that sort of book (Seinlanguage anyone?) serves primarily as a souvenir for fans happy to revisit their enjoyment of an already celebrated performer, My Life As A Goddess will hopefully serve as many readers’ introduction to its author.

Branum brings a well-ticked checklist of outsider bonafides to the comedy scene. He is gay, fat and was raised in the distinctly non-cosmopolitan environs of Yuba City. He’s Jewish, which one might argue doesn’t count as ‘outside’ in comedy, but he’s a not a big city deli-and-sleepaway camp Jew; he’s a grew-up-in-farm-country-surrounded-by-rednecks-and-Punjabi Sikh farmers Jew.

While spiked with humorous attitude and observations, Goddess offers a singular mix of self-searching personal inquiry, outspoken sociopolitical opinion, and piercing philosophical exegeses of mass media artifacts.

“But if you only know me from being a talking head on Chelsea Lately, you may not be ready for my queer theory,” jokes Branum, who counts his years as a writer and onscreen presence on Chelsea Handler’s show as his biggest career breakthrough to date and Handler herself as an important mentor.

Within its extremely loose structure, Branum’s book has room for a brilliantly nuanced analysis of The Man Who Shot Liberty Vallance, his dad’s favorite film, which also serves as a meditation on their tempestuous father-son relationship; and a surprising ten-page tangent on Canadian history, which Branum ultimately reels in and connects to his own life.

“That actually does have something to do with me as a fat person and a gay person,” Branum reiterates during our conversation. “Here’s this country of 30 million people who are right next to us and we never pay attention to them. Who do we choose to pay attention to? Who do we ignore? Those are questions that really point to cultural arrogance and self-absorption.”

“That actually does have something to do with me as a fat person and a gay person,” Branum reiterates during our conversation. “Here’s this country of 30 million people who are right next to us and we never pay attention to them. Who do we choose to pay attention to? Who do we ignore? Those are questions that really point to cultural arrogance and self-absorption.”

Branum writes compellingly of being electrified as a teenager by Eddie Murphy’s concert film Raw and then re-watching it recently only to notice how it brims with blatant homophobia.

“I’m still thinking about that,” he says, “How something so dismissive of me could also be so inspiring. It made me love stand-up and hate myself.”

That sort of tempered, self-questioning response is typical of Branum’s thought processes. A Poly Sci degree from U.C. Berkeley and law degree from the University of Minnesota are at work behind the scenes of his joke-writing.

“A friend of mine teased that I don’t write jokes, I write essays about jokes. But it’s actually true. When I write stand-up, I write verbosely at first and then I chop it down, compress it.”

Something Branum has been thinking a lot about lately is the continuing absence of any big name gay male comics in American culture. He points to Tim Dillon and Solomon Georgio among other examples of top-notch gay stand-ups who do a wide range of material, but who aren’t getting the booking or exposure that straight comics get.

Part of it, thinks Branum, is a longtime curdling of gay men’s interest in supporting stand-up.

“Look, stand-up comedy has not been a safe place for gay people. There were always jokes being made about us and how disgusting we were supposed to be.”

His views have some common ground with those of Hannah Gadsby, the Australian lesbian comic whose current Netflix special is all the rage-and ends with her seeming to renounce stand-up as a form.

“Don’t throw in the towel on comedy. Why does comedy have to be the villain here?” wonders Branum. “You can always write better comedy and be more challenging. You don’t have to spoonfeed an audience exactly what they want.

“Don’t throw in the towel on comedy. Why does comedy have to be the villain here?” wonders Branum. “You can always write better comedy and be more challenging. You don’t have to spoonfeed an audience exactly what they want.

“It bothers me that the most significant comedy special by a queer person is the one that distances itself from comedy. It makes queer people feel like we’re somehow better than comedy. But if we step away, its not going to change. Partly because stand-up has been homophobic for so long, gay men don’t that excited about gay male comedians. We love female comedians.”

And, of course, drag queens.

“It’s a beautiful moment for drag, and I’m glad to see it,” says Branum, “It’s a part of our culture that’s been misunderstood for a long time and people are getting to know it. There are thoughtful queens like Ben de la Crème and Alaska and Jinx Monsoon who are doing great things.

“But because a lot of drag is still done in gay bars, where people are drunk and trying to fuck, a lot of drag comedy tends to rely on short, loud, Catskills stereotypical kind of jokes.

“When there’s a drag show,” says Branum, “At least we know it’s for us. We know that the performer is not going to humiliate us. I’m lucky because I’ve had exposure on television. But there’s still not much space for gay stand-up comedy in our community. Gay men need to get better about consuming material by and about the whole spectrum of gay men.”