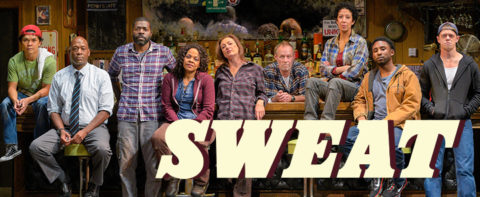

The audience feels a jolt when the N-word is shouted during the opening scene of “Sweat.” But Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer-winning drama defies initial expectations. Much more than a righteous play about the wrongness of racism, the powerful production now at A.C.T’s Geary Theater is about the destruction of blue collar communities. The dehumanizing toll of unemployment. The pain of having your self-image pulled from beneath you like a rug.

It’s about people who get slammed so hard that they break. And how racism crawls out of the cracks in broken people.

That opening scene, set in 2008, in the fading steel town of Reading, Pennsylvania, toggles between Jason (David Darrow) and Chris (Kadeem Ali Harris). Both in their late-twenties, they’re individually meeting with a stern but encouraging parole officer. While in prison, mild-mannered Chris, who is African-American, took up Bible study. High-strung Jason took up with white Supremacists. Eight years prior, before the crime they committed together, Jason and Chris were best friends.

So were their mothers, Tracey (Lise Bruneau) and Cynthia (Tonye Patano), who we meet along with a third pal, Jessie (Sarah Nina Hayon), in a flashback to 2000, just ahead of big trouble. They’re carousing together at the neighborhood tap—where most of “Sweat takes” place—celebrating Tracey’s birthday. They always celebrate their birthdays here, and they probably drop by for a drink every day.

Their bar, like their town, is a place where traditions matter. You can see it in the life-worn details of Andrew Boyce’s beautifully detailed set: the faded red vinyl upholstery in the booths, the green neon Yuengling beer sign, the felt Phillies pennant and old Dr. J. poster tacked to the wood-paneled wall.

The women are longtime coworkers on the same factory floor where their fathers once worked and where their sons are just getting started (Chris is also taking night school classes, sensing an eventual need to move to a newer, wider world). Their identities are tied to lives of routine. They’ve never expected much, but to a large extent, their expectations have been met.

Yes, Tracey once had hippie dreams, roaming from Istanbul to Lahore to Kandahar and beyond; but her late husband’s cancer has left her back where she started, grateful, at least, for union medical coverage. And Cynthia is estranged from her husband, Brucie (Chiké Johnson), whose hollow mien and haunted stare show the damage done by two years locked out of work in a labor dispute. But the old friends keep plugging away, supporting each other in sisterhood, settled with their lot.

The great unsettling begins when Cynthia wins the rare opportunity to move off the floor for a supervisory job. A pawn in a bigger game, she briefly becomes one of “them.” Her friends feel betrayed. And in their contempt, they take note of their sisters’ skin color. The rift grows deeper as management demands that labor take a precipitous 60% paycut, or lose the entire factory to Latin America—either by watching it move to Mexico, as other local businesses have, or by seeing their jobs taken over by the Rust Belt’s immigrants, folks like Oscar (Jed Parsario), the quiet barback they’ve never really noticed before, for whom $11 an hour would be a raise, not the crumbs of entitlement.

The great unsettling begins when Cynthia wins the rare opportunity to move off the floor for a supervisory job. A pawn in a bigger game, she briefly becomes one of “them.” Her friends feel betrayed. And in their contempt, they take note of their sisters’ skin color. The rift grows deeper as management demands that labor take a precipitous 60% paycut, or lose the entire factory to Latin America—either by watching it move to Mexico, as other local businesses have, or by seeing their jobs taken over by the Rust Belt’s immigrants, folks like Oscar (Jed Parsario), the quiet barback they’ve never really noticed before, for whom $11 an hour would be a raise, not the crumbs of entitlement.

Profit-driven pressure comes down on these women, crushing their solidarity along with their souls. In short order, they lose not just their work, but their deep-rooted identity as working class Americans. And in this class war, the women revert to a bunker mentality—an Archie Bunker mentality, the sort of reflexive, self-protective racism that Cynthia acknowledges was typical of their fathers’ generation, but seemed to lessened in their own. It’s a terribly misguided effort at self-soothing, as are the opioids and excess alcohol that only end up compounding their misery.

Jason and Chris experience a compounded misery, too, losing not only their jobs, but the bedrock of community and family their mothers had always exemplified. Where Tracie and Cynthia collapse in on themselves, their sons lash out, irreversibly.

As written by Nottage and directed by Magic Theater artistic director Loretta Greco, “Sweat” plays with a detailed, almost documentary realism rarely seen in recent seasons on Bay Area stages. This is solid, old-fashioned American social drama in the tradition of Arthur Miller and Eugene O’Neill, but with female characters now at center stage. Perplexingly, while women are at the heart of this story, Nottage both opens and closes her script with scenes featuring only men.

Uniformly well acted, “Sweat” invites you to empathize with each of its characters, even when their behavior is at its worst, and to consider the degree to which racism emerges as a symptom of a larger disease.

Originally published in the Bay Area Reporter