I finally made it to the room where it happens when “Hamilton” officially opened its second San Francisco engagement last Thursday night. Well, one of the rooms. In addition to continuing long runs on Broadway (3 1/2 years and counting) in Chicago (more than 2 1/2 years) and in London (just past its first anniversary), two separate touring companies are taking Lin-Manuel Miranda’s juggernaut to dozens of cities across the U.S.—on the day this article prints, they’ll be Ham-ing it up in Cincinnati and Tampa.

If you’ve yet to see the show and are wondering whether to take the plunge this go-round, you probably have some of the same questions on your mind that I had last week, first and foremost “Does it live up to the hype?”

What I can tell you is this: Even four years, a half-dozen companies and hundreds of cast members beyond its Public Theater debut, “Hamilton” hits the Orpheum with the crackling energy of a lightning strike and the exhilarating freshness of new ozone. It’s alive in a way that live theater rarely is, especially in the context of a well-established brand name property. The ensemble tears into Miranda’s complex material, coming off as if its not performing a script, but experiencing the events of this story for the first time. You’ll feel like an eyewitness more than a spectator.

The second big question you may have, given “Hamilton”‘s heralded rap vernacular, “Will I be able to follow the plot?”

Its a fair question. The answer is yes. What you won’t be able to do, though, is catch every lyric. But you don’t savor individual notes the first time you hear a symphony either; you let it pour over you and soak in the totality, appreciating its overall shape and sweep, while taking particular pleasure in those details most notable to you. (Mine was a line that whizzed by about “the afterbirth of a nation”).

Miranda has been rightly praised for using familiar musical genres to draw younger audiences into unfamiliar realms of history and theater, the flip side of that assessment is equally important: By leveraging a story that—in its broad outline—is already familiar to most American audiences, “Hamilton” gives the rap-avoidant and hip-hop-phobic an opportunity to appreciate the wit and nuance these forms can incorporate.

The verbal avalanche of “Hamilton”‘s densest numbers is also entirely true to its subject: Throughout the show, Alexander Hamilton’s antagonists—and even his admirers—criticize him for his workaholism and volubility, manifested primarily in oral and written logorrhea. “Non-Stop,” the spectacular closing number of Act I is dedicated to debating the pros and cons of this excess. Miranda’s model and motives are baked into the show, to delicious effect.

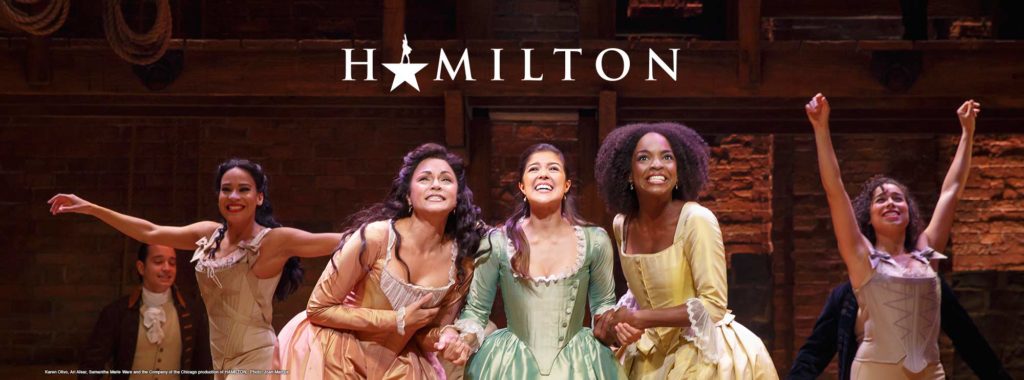

And, for all the attention “Hamilton” has received for its feverish syncopated raps, the show is also rich in R&B and pop- influenced melodic hooks. The Schuyler sisters’ tight, silky signature song has Eliza—the future Mrs. Hamilton (Julia K. Harriman), Angelica (Sabrina Sloan) and Peggy (Darilyn Castillo, who also plays femme fatale Maria Reynolds) doing sweet, smart, self-confidence that’s ticklishly evocative of Destiny’s Child. Simon Longnight, brings a pinch of Prince—and a hairdo straight outta Kid ‘N’ Play—to his sassy Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson; the historical figures’ French connection underscored by the dual role. “It’s Quiet Uptown,” the duet sung by Hamilton (Julius Thomas III) and Eliza in the wake of their son Philip’s death is at once gingerly and wrenching, plumbing the depths of grief and the interdependencies of marriage. It aches and shimmers like the best Broadway ballads.

You won’t find a weak link in the cast, but there’s hypnotic power in the commanding performances of Donald Webber, Jr. as Aaron Burr; Isaiah Johnson—translating George Washington into Doberman Pinscher; and Brandon Louis Armstrong playing Hercules Mulligan and John Adams with the voice and physique of a kettle drum.

Thomas Kail’s direction and Andy Blankenbuehler’s choreography keep the company of more than 20 in motion as constant as history’s march. Their physical motifs marry to orchestrator Alex Lacamoire’s musical ones, helping illuminate the influence of one incident upon the next. And Paul Tazewell’s body-conscious colonial costumes help make the handsome, self-possessed players sexier than anything you’ve ever seen in a history book.

One “Hamilton” question that you still may have that I honestly can’t answer is “Is it worth the money?” Let me say this: While not life-changing, the story of the first U.S. treasurer is life-enriching in a way that no other work of musical theater in San Francisco has been since the last time this one stopped by. Its also a work that begs to be unpacked and examined for far longer than the three hours one sits through a performance. If you’re committed to making the most of the arts, a ticket combined with a download of the cast album will be most worthy when appreciated as a longterm investment.

Originally published in the Bay Area Reporter