The below is a review of last year’s California production of Soft Power. The show begins its first New York run at the Public Theater on September 24, 2019.

A provocative popcorn machine of intellectual entertainment, “Soft Power,” playing the Curran Theater through July 8, delivers a rat-a-tat fusillade of sociopolitical satire, musical parody, and autobiographical angst. Written by David Henry Hwang with music by Jeanine Tesori, this surreal extravaganza explodes directly into the here-and-now with hot takes on the 2016 election (Hillary Clinton is a singing, dancing, major character) and the racist attack that Hwang (himself a character, played by Francis Jue) experienced in its aftermath.

“Soft Power” also hums with a deeper thesis about white America’s long-held cultural prejudices against Asians, Exhibit A being the broad-stroke exoticism of “The King and I.” That Rodgers and Hammerstein classic, for which playwright-Hwang and character-Hwang express both admiration and consternation, is turned inside out in “Soft Power”‘s fantasy musical scenes. Chinese businessman Xue Xing (Conrad Ricamora) travels to a 2016 America populated entirely by blond-haired, gun-toting, southern-accented men and blonde-haired, gun-toting, underappreciated women.

Ricamora, who plays the HIV+ Oliver on “How To Get Away with Murder,” has a velvet vocal tone and remarkable range that give even his lighter songs a rich, almost operatic feel. Like schoolmistress Anna in “King and I” Thailand, the well-intentioned foreign interloper Xue is the single fully realized character in these numbers. The ensemble of monochromatic “ethnic” natives have much to learn from the more civilized society he comes from.

Musical scenes form the most dominant of four nested art-vs.-reality storylines within “Soft Power.” But this conceptual complexity is rarely off-putting. Some audience members will revel in dissecting the show’s structure, but it’s easy to opt out of overanalysis. You can indulge Hwang in his elaborate Mobius striptease while keeping your focus on the pageant of laugh-out-loud set-pieces on sets designed by David Zinn, who just won a Tony for his wackadoodle “SpongeBob” seascapes.

Here’s pre-election Hillary (Alyse Alan Louis) campaigning in a Busby Berkeley fantasy McDonald’s. She emerges on a giant burger, and when serious policy discussion bores the crowd, balances an order of fries on her forehead, a seal trained into submission by convention and cable news.

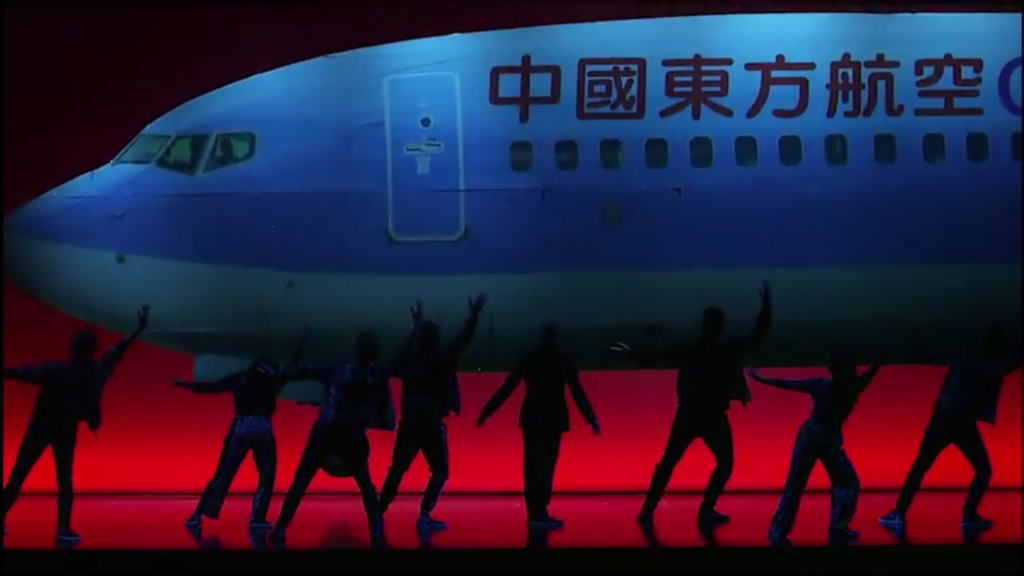

Here are Xing and Hillary waltzing a pitch-perfect parody of “Shall We Dance” from “King and I.” Here’s the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (Jon Hoche) rattling off a “Schoolhouse Rock”-style patter song in a miserable attempt to rationalize the U.S. electoral process. And here’s a colloquium in 2066 Shanghai during which Chinese academics lay claim to the Broadway musical as a part of their national heritage.

Louis gives a breakout star-turn as Hillary, pulling faces like Carol Burnett, dancing like Ginger Rogers, and somehow, amidst the lunacy, summoning up unexpected moments of sorrow and solitude.

The ensemble cast is glorious, with comedy chops worthy of “SNL” at its sharpest, and singing voices that help make even novelty lyrics sound sublime. I say “help” because, along with further assistance by music director David O and a lush 21-piece orchestra, the heavy lifting is done by Jeanine Tesori.

Tesori, best-known for intimate, idiosyncratic musicals “Fun Home,” “Violet” and the Tony Kushner-scripted “Caroline, Or Change,” proves the adage that you have to master the foundations before you build on them. With grand songs incorporating nuanced stylistic echoes of not just “The King and I,” but also “The Sound of Music,” “The Music Man,” “My Fair Lady” and more, she demonstrates a deep understanding of Golden Age musical tropes.

Hwang and Tesori share credit for the humorous lyrics, which could easily have been carried by the sort of smart pastiche tunes found in Hasty Pudding Club lampoons. Instead, Tesori has written genuinely swoon-worthy sparklers. They, along with Sam Pinkleton’s thoughtful choreography, lift “Soft Power” to levels of pleasure that transcend its academic smarts.

Billed as “A Play with Music,” “Soft Power” indeed plays beautifully with music. It also lets us watch Hwang play with ideas that he’s been exploring throughout his career. His play “Yellow Face” was a response to the controversy over the casting of Jonathan Pryce as the lead Vietnamese character in the musical “Miss Saigon.” Hwang radically revised the script of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Flower Drum Song” to alleviate its reliance on Chinese stereotypes. His Tony-winning Broadway debut “M. Butterfly” challenged white preconceptions of Asian masculinity.

In “Soft Power” Hwang continues to dig, revealing new complexities within subject matter that compels him. An American success story, he was attacked, post-election, in a racial hate crime, and he uses this show to mull over what feels like perpetual insider/outsider status. It’s a notion that’s also embedded in the show’s musings about the differences between Chinese, Chinese-American and dominant American culture (i.e. White with a little hip-hop thrown in).

But the fact that Hwang is able to appreciate the nuances of these issues doesn’t mean they can all be effectively addressed in a single work of art. Despite a noble effort, director Leigh Silverman isn’t quite able to wrangle Hwang’s abundance of ideas into a shapely whole. There are sometimes abrupt shifts in tone from scene to scene, and monologues delivered by Jue, playing Hwang, throw a wrench at momentum. At these moments and others, including unnecessary dialogue about male-male affection in which the playwright waves his liberal flag, it feels as if Silverman holds back on reining in Hwang’s restless mind.

But in the end, even more than Tesori’s transporting music, it’s the fecundity of Hwang’s mind that makes “Soft Power” a thrilling work of theater and advocacy. The play’s kernels of truth sometimes burst forth so fast and furious that they’re hard to digest. But on to the next, on to the next. As an audience member, you’re given a jumbo bucket of thinking to do, with plenty to take home and chew on afterwards.