Originally published in the Bay Area Reporter

Originally published in the Bay Area Reporter

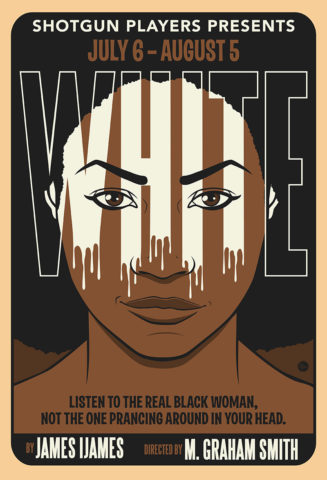

Two audacious works of theater with art and identity at their cores are currently playing Bay Area stages. Where the San Francisco Playhouse’s excellent “Sunday in the Park with George,” reviewed here last week, is cool and canonical, Shotgun Players’ “White” is emotionally hot and utterly of the moment.

Playwright James Ijames’ biting contemporary comedy, sleekly directed by M. Graham Smith, begins with Gus (Adam Donovan), a struggling young gay painter, who persuades Vanessa (Santoya Fields), an African American actress, to assist him in a scam. After college chum and curator Jane (Luisa Frasconi) excludes him from a major exhibition of new artists because he is a “white dude,” Gus asks Vanessa to pose as an artist and submit some of his paintings in the hopes of winning a place in the show.

If you think making that request is skating on thin ice, just wait. You’ve bought yourself a ticket to the Identity Politics Capades. Gus doesn’t merely want Vanessa to serve as his stand-in, he wants her to play a coarser, brasher, less articulate woman than she actually is: a “blacker” black person.

Oblivious and patronizing, he assures her he knows what he’s doing. After all, “Every gay man has a black woman inside,” says Gus, who claims Diana Ross as his spirit animal. The fairy’s godmother, also played by Fields, manifests onstage in several laugh-out-loud interludes, all sugary whispers and empty-caloried affirmations.

Why self-possessed Vanessa would ever accept Gus’ ill-considered offer requires the most difficult suspension of disbelief Ijames asks of his audience. Because she’s an actress, and this is a role-playing challenge? Because this is a comedy, so what the hell?

In any case, we are faced with the skin-crawling spectacle of Gus playing racist Henry Higgins to Vanessa’s Eliza Doolittle. On goes the Afro wig and up goes the sass factor. Stand back for the finger-wagging and “Oh no you diiin’t!” jive. This new persona will go not by Vanessa, but by “Balkonaé.” Higgins’ “I think she’s got it!” becomes Gus’ vainglorious “Whoop, there it is!”

While the play’s script could use a bit of refinement in regard to Vanessa’s initial motives and Gus’ sometimes over-the-top immaturity, Shotgun’s production goes a long way toward smoothing over the writing’s rough spots. Director M. Graham Smith keeps the action moving swiftly and seamlessly, thanks in no small part to Nina Ball’s elegant sliding-paneled set and Santoya Fields’ remarkably fluid transitions between Vanessa, Balkonaé, and Diana.

Ijames’ writing deepens as the play progresses. Just when he seems to be settling into righteous, rather conventional P.C. liberalism, he takes a fascinating turn. Rather than maintaining focus on the annoyingly tunnel-visioned Gus, he turns to the relationship between Vanessa and Balkonaé, who indeed wins a place in the art exhibition.

Ironically, in playing a role that meets the white art establishment’s preconceptions of a black woman artist, Vanessa begins to feel empowered. She’s as seduced by Balkonaé as museum leaders are, and disinclined to let Gus claim any victory in his ruse. By leveraging stereotypes to her advantage, she has, however fleetingly, got a leg up on the privileged likes of Gus.

The play is further peppered with complexity by Gus’ domestic life. His doting partner Tanner (Jed Parsario), an Asian-American schoolteacher, is unsurprisingly ruffled by Gus’ resentment over the rise in opportunities for artists of color. In one of the show’s smartest, slyest exchanges, one that will be familiar to members of interracial couples, the pair jostles with the fact that they’re not merely “us” or “the same.”

The play’s audacious final scene finds “White” becoming “Black Mirror,” in more ways than one. In a twist worthy of television’s dark sci-fi anthology, questions of “us” and “the same” return to Vanessa and Balkonaé. Standing before a museum audience of scenesters and donors, they literally debate each other, two characters trapped within one body, one wanting to speak her truth, the other willing to say whatever it takes to be heard.