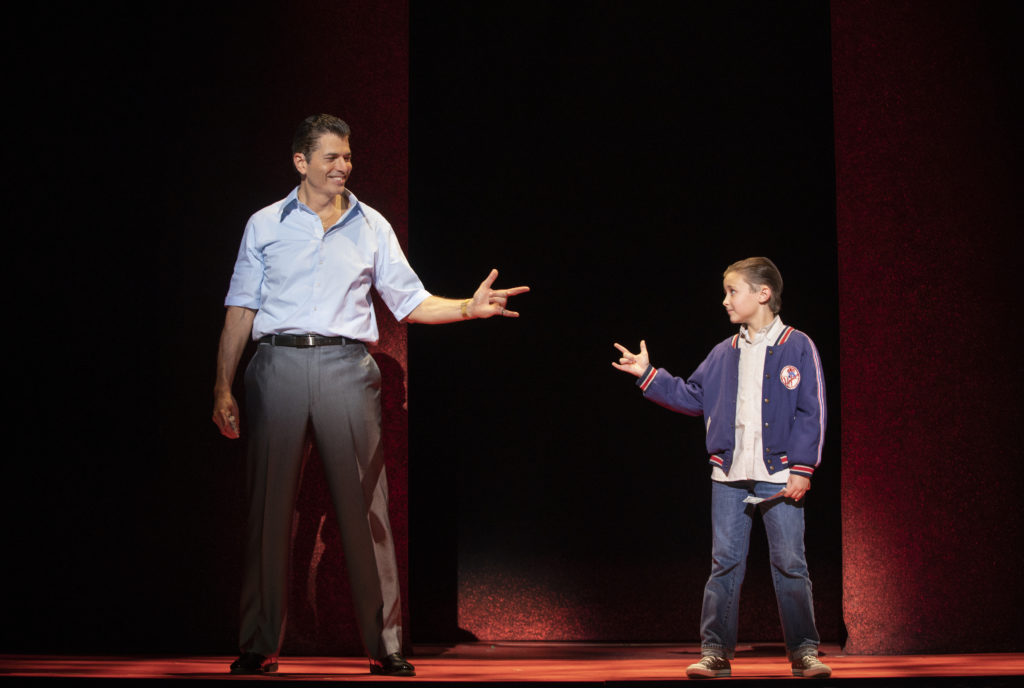

Lorenzo, Young Calogero and Rosina (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Straightforward, familiar and enormously satisfying, “A Bronx Tale” is the relatively rare contemporary musical that exudes winning sincerity more than winking self-consciousness. Now playing at the Golden Gate Theater, this 1960s coming-of-age tale—adaptated from Chazz Palminteri’s autobiographical one-man show and its excellent 1993 film adaptation—offers old school entertainment built around a core curriculum of sturdy moral lessons.

Set in an Italian enclave of New York’s northernmost borough, the show has a urban stoop and doo-wop milieu that’s instantly evocative (and, at first, one may fear, derivative) of two other 21st century Broadway hits, “Jersey Boys” and “Hairspray” (with which “A Bronx Tale” does share a racism-themed plot line).

But “A Bronx Tale” avoids the shadow of the Valli of glitz and steers away from “Hairspray”‘s more lighthearted aesthetic thanks to Palminteri’s nuanced main characters and a cast of committed, no-showboating performers.

At the heart of the show is a platonic/paternal male love triangle among teenage Calogero (Joey Barreiro), his bus driver father, Lorenzo (Richard H. Blake) and Sonny, the local mob capo (Joe Barbara) who lords over their block and holds court at the corner bar.

The music, composed by Alan Menken with lyrics by Glenn Slater, helps audience members stay as committed to the story as the cast is. Integrating elements of streetcorner acapella, sixties’ R&B, and supper club crooning deeply evocative of the era being portrayed, the songs in a “A Bronx Tale” are all original; they advance the plot and reveal aspects of the characters’ personalities. That’s a major contrast to other musicals set in the same era but built around preexisting hit oldies (“Jersey Boys”, “Motown”, “Beautiful”). While well-known pop songs can help ensure a degree of commercial appeal, they often allow shows to use audience members’ personal nostalgia as a crutch in lieu of strong onstage narrative.

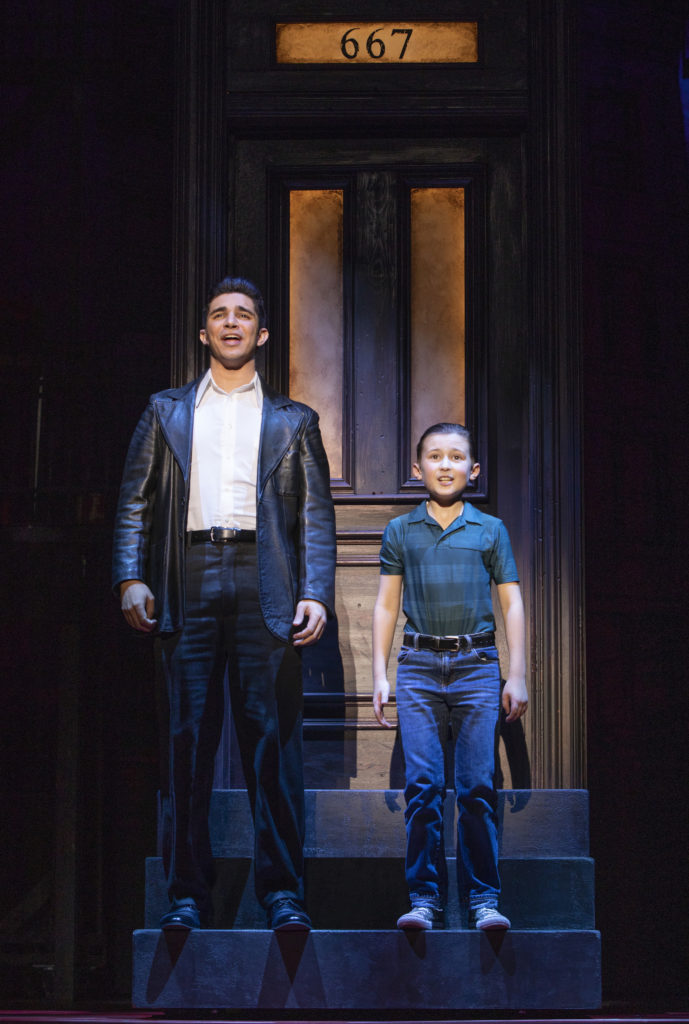

Sonny and Calogero (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Menken doesn’t leave us with an indelibly hummable tune here, but Slater’s lyrics do much more than carry the story—they deliver a consistent linguistic buzz: “Carmelite sisters scream at their transistors every time the Bombers score”; low-level wiseguys are actually “dumba than a lumpa mutts-a-rella.” Poetry like that is enough to make you forgive the boilerplate uplift of “A Bronx Tale”‘s one false-note song, “The Choices We Make”, a choral finale that feels more like an Irish sea-shanty than Italian nostalgia.

Like most of the music, Beowulf Boritt’s confidently simple sets work in service of the story without distracting from it. Translucent scrims of urban architecture and moveable towers that mimic the windows and fire escapes of tenement alleyways accentuate the tightly overlapping private and public lives of the characters, but never upstage them.

In the show’s early flashback scenes, we meet Calogero at age nine (Frankie Leoni), when he’s largely naive to mafioso morality. Lorenzo’s guidance to “Look To Your Heart” and live with compassion is somewhat lost on his son. After comparing his honest, earnest, hardworking dad to Sonny, with his fancy car, free-flowing cash and revered neighborhood status, Calogero naively opts to emulate the bankrolled role model. “The working man is a sucker,” Sonny tells the kid, who, in short order, becomes his mascot, and his errand-runner on a dead-end road.

Blake is superb, evincing a beefy, sweet masculinity and Barbara gives us a lived-in, off-the-cuff Sonny so deftly rendered that audiences are able to hate his outer menace even while recognizing his inner mensch. Barbara gets to the show’s cleverest song—”Nicky Machiavelli” a statement of Sonny’s personal credo that’s also a nifty pastiche of “Mac the Knife”—which he delivers with near-perfect Sinatra phrasing that’s revisited in his second-act solo “One of the Great Ones.”

Like Blake and Barbara, Leoni, who is ten, previously played his role in the Broadway production of “Bronx Tale”, and the experience shows. Young Calogero is no on-and-off opportunity for cuteness, its a substantial role with four significant songs. Not only is Leoni’s singing impressively articulate, he also imbues the character with an endearing-yet-charismatic swagger that crisply syncs with Barreiro’s physical interpretation of Calogero at 17. The pair sing and dance together in “I Like It” quite convincing as the same person at different ages. (At some performances, Young Calogero will be played by Shane Pry).

Sonny and Young Calogero (Photo: Joan Marcus)

As teenage Sonny, Barreiro is onstage for almost the entire evening. He seems a bit off-balance narrating the childhood flashbacks early in the show, but later his rough-and-tumble charisma as the youngest member of Sonny’s squad and moony charm when smitten by Jane (Brianna-Marie Bell), an African-American schoolmate, in the show’s romantic (if over-accelerated) subplot, win us over. In fact, his early awkwardness is largely baked into the show’s slightly flawed structure

As originally conceived by Palminteri, “A Bronx Tale” was a monologue of his own reminiscences; nine- and 17-year-old Calogero representing the youth of the now-successful playwright/actor addressing his audience. Here, instead of the forced perspective of a highly accomplished adult narrator looking back, we get an average teenager describing his hardly-distant childhood. This otherwise loyal adaptation might have benefitted by taking a more linear approach to its storytelling.

Calogero, at 17 and at 9 (Photo: Joan Marcus)

One also wishes that the tension-generating interracial teen romance were given more room to breathe. So much plotting is packed into the show’s second act that, other than Jane, with her bold streak and Bell’s fine-grained singing voice, the black characters are left far less defined than the white ones.

Also off to the margin of this boys-to-men story is Rosina, Calogero’s mother (Michelle Aravina). But in a few well-slung zingers, a sharp reprimand of her son, and a shimmering second act reprise of “Look To Your Heart”, Aravina gives her a distinct and memorable presence.

Still, these quibbles with “A Bronx Tale” are offered not so much as demerits but as wishful thoughts on how a pretty terrific show might have been “One of the Great Ones”. Still, pretty terrific is pretty terrific. Capiche?

Originally published in the Bay Area Reporter