“I spent countless hours in my bedroom pretending to be Eva Peron,” recalls first-time novelist and six-time Tony nominee Chad Beguelin of his cast album-filled childhood in Centralia, Illinois.

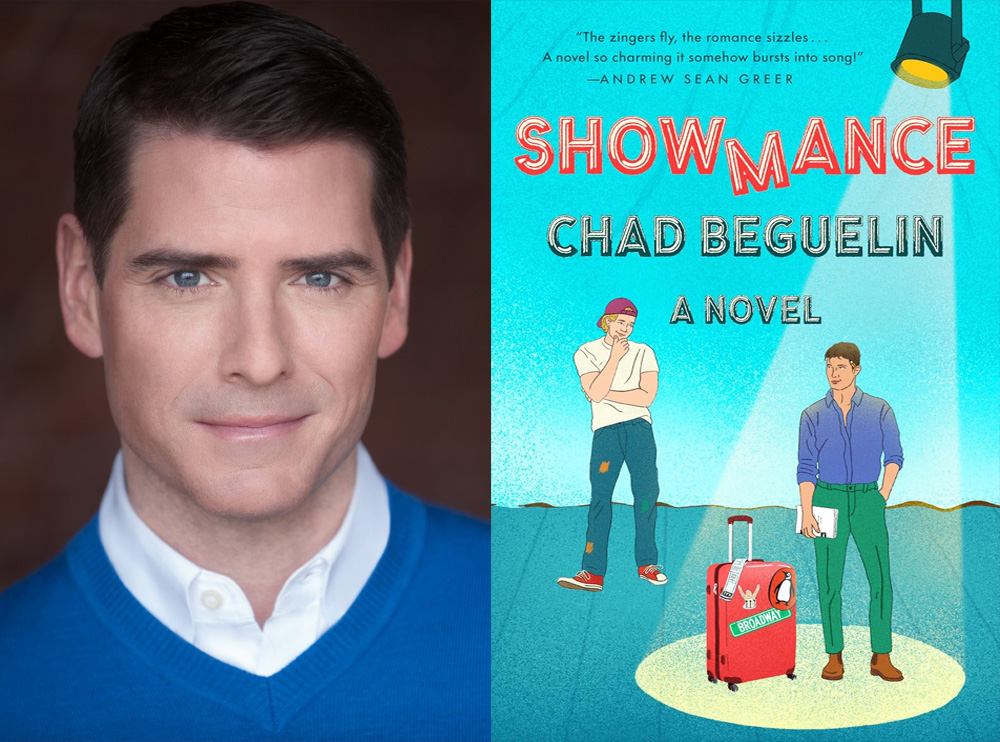

A Broadway lyricist and book writer whose collaborations include “The Prom“, “The Wedding Singer,” “Elf: The Musical,” and Disney’s “Aladdin,” Beguelin writes what he knows and has always loved in his literary debut, “Showmance,” a romantic comedy about a gay Broadway theater artist.

The novel follows the rude trajectory of writer/composer Noah Adams after his first Broadway production, based on “King Lear” and set in outer space, is panned by the critics and closes after one performance.

On the same night as this simultaneous debut and debacle, Noah’s farmer father suffers a heart attack. Our beleaguered hero heads back to his midwest hometown, only to meet further adversity: He gets long-distance dumped by his New York boyfriend and discovers that the hunk who bullied him for being gay in high school has become his father’s favorite farmhand.

There’s never a doubt that all will work out in the end for Noah, and the book’s plot hits largely familiar beats. But with the entertaining snap of his dialogue and the endearing sap of his characters, Beguelin crafts a satisfyingly old-fashioned story infused with contemporary mores.

Fewer rules, less waiting

In a recent interview with the Bay Area Reporter, Beguelin acknowledged the differences he found between writing the book of a musical and writing an actual book:

“The main thing is that, with musicals, you’re always working with collaborators who you bounce ideas off of. On every show I’ve worked on, the whole creative team gets together and creates a very detailed outline where we try to figure things out, especially where the songs belong.

“It’s called song spotting. Then the songwriters and book writers work independently for a little while, and then they come back and start to put things together.

“Writing the novel, it was just me. I’d experiment and second-guess myself and switch things around until I had something I liked.

“I’ve learned that fiction writers talk about either being ‘planners,’ who outline everything in advance, or ‘pantsers,’ who go by the seat of their pants. I definitely realized that I was a pantser.

“It was exciting for me to just explore on the page and not be certain about what would come next because it’s so different from how I work in theater, especially when it comes to writing lyrics.

“There are so many rules with lyrics. Every word matters, and it’s also got to rhyme, and you want it to rhyme in new, surprising ways. It can feel like building a ship in a bottle; you’ve got very little room to move in.

“So, in some ways, writing a book felt totally freeing for me. I had so much latitude.”

Beguelin also noted that the solo nature of fiction writing offers a welcome counterpoint to the sometimes lumbering machinations of theater production.

“When you’re working on a new show,” he explained, “the process is so stop-and-start. You have to wait for a director or actor’s schedule to work out; you have to wait to find the right theater to be available to make things work economically. There’s a lot of waiting.

“But when I had the idea to write a novel, I realized that I didn’t have to wait for anything. I could work as quickly or slowly as I wanted. It was very satisfying to be able to set my own pace.”

Writer’s blocking

Ironically, it was only after he began working with Marie Michaels, his editor at Penguin Books, that Beguelin realized he needed to take responsibility for some of the work that directors tend to handle in the theater.

“She would tell me that I was missing the blocking. ‘Where is everybody?’ she’d ask, ‘Where are they all standing?’ There’s a scene where there’s a big kiss and she asked me ‘Where are Noah’s hands? I can’t see what’s going on.’ I had to take charge of making things visually clearer for readers.”

On the other hand, said Beguelin, Michaels seemed impressed by the way the stakes kept relentlessly rising for Noah throughout the novel.

“But that’s something you have to do in a musical. You’ve got to keep getting your characters into such a heightened state that they can’t do anything but burst into song. I do think that probably affected the way the plot develops in the book.”

Beguelin is currently developing a new musical called “Horrible People,” a mistaken identity farce that skewers both one-percenters and social climbers (A recent workshop with Tony winners Sutton Foster and Beth Leavel was well received), but he hopes to continue writing novels as well.

“And, of course,” he says, “I’d love to do ‘Showmance’ as a musical.”