Loaded with ethical trap doors and secret passages, Zak Salih’s debut novel Let’s Get Back to the Party (Algonquin. $25.95. www.zaksalih.com), is one of the most provocative and nuanced explorations of contemporary gay life to be published in the last few years. Alternately narrated by Sebastian and Oscar, two thirtysomethings who briefly explored their burgeoning homosexuality together as children but have been out of touch for many years, the novel toggles between Oscar’s revulsion at Obergfell-era gay assimilation and Sebastian’s jealousy of the sense of freedom and normalcy that he, a high school teacher, senses in his own queer students. Oscar looks backward as Sebastian looks forward, both full of loneliness and longing. While the counterbalance of these characters feels a bit over-engineered at first, Salih complicates matters by adding two pivotal secondary characters to the mix: A once-celebrated sexagenarian author of thinly fictionalized, sexually charged novels (clearly based on Edmund White) who Oscar aspires to emulate; and a 17-year-old high school senior who Sebastian finds himself ashamed to be falling for. An eerie Hitchcockian sense of suspense builds—without ever quite resolving—throughout the book as the Oscar and Sebastian’s lives begin to criss-cross in the gay enclaves of Washington, D.C. and its suburbs. Salih deftly spins strands of narrative that stretch from the Stonewall riots and Chelsea Piers to the Pulse massacre and hook-up apps, entangling two compelling characters who are lost between these eras.

While its title quotes from Romeo and Juliet, These Violent Delights (Harper. $27.99. www.micahnemerever.com) centers on a doomed adolescent romance more evocative of Herman Hesse than William Shakespeare. Like Hesse’s Demian and Steppenwolf, this is a book in which navel gazing begets staring into the void. Debut author Micah Nemerever steeps readers in the simultaneously rebellious and self-flagellating mindsets of working-class Paul and wealthy Julian, two Pittsburgh college students in the early 1970s who fall into a dangerous state of codependence while trying to cope with with family trauma. Paul’s father, a police office, has committed suicide shortly before novel begins and Julian, we gradually learn, along with Paul, comes from a massively wealthy and monstrously manipulative clan. Along with the mutually sadomasochistic sex that fuels the boys’ attachment to each other and disassociation from their daily lives, they bond over a mind-game in which they imagine methods of murder and try to choose ideal victims for their perfect crime. While the main pair’s twisted relationship and philosophical conversations dominate the book, Nemerever embroiders the edges of this darkness with a finely wrought portrait of Paul’s grieving mother, simultaneously worried by her son’s nihilism and homosexuality, yet grateful that he has formed a close friendship. Nemerever’s ability to precisely dissect such complex states of mind makes him an author worth watching.

A strange, slim, shiver-inducing volume, Yukio Mishima: The Death of a Man (Rizzoli. $55. www.rizzoliusa.com) is a hardbound suicide note that has come to light 50 years after its subject’s demise. In November of 1970, Mishima—the iconic Japanese writer, actor and social provocateur who first rose to fame with the publication of his homoerotic autobiographical 1949 novel Confessions of a Mask—committed ritual suicide, seppuku. It was the bold final act in the life of a self-created character who viewed his own life as a single overarching work of art. During the year leading up to his death, Mishima personally conceived and art-directed the 80 photographs shot by Kishin Shinoyama that are published here: A series of images in which Mishima is costumed as soldier, fencer, fisherman, athlete and other archetypal male figures and posed as if each of these characters are dead. We see him in a leather jacket, sunglasses and helmet sprawled on cracked asphalt, apparently thrown from the motorcycle that lies off to his side. We see him wrapped in barbed wire, pierced with a sword, hanging from a noose, and, most chillingly, gutting himself with a large knife while in traditional samurai garb, as if conducting a dress rehearsal for his actual death. Morbid as these pictures are, they are also suffused with homoeroticism—Mishima’s characters are often fully or partially nude—and even a creepy version of Village People camp. A head-scratcher and loin-stirrer all at once, this book is as haunting and confounding as Mishima himself. Hopefully it will pique curiousity and lead more gay readers to explore his undeniably brilliant novels and poetry.

Bryan Washington’s Memorial (Riverhead. $27. www.brywashing.com), one of the most acclaimed debut novels in recent years, is full of characters we rarely meet in fiction. And when we do meet them, they’re usually not in the same books. Overweight gay men, short order cooks, daycare staffers, sero-mixed couples and even an alcoholic meteorologist are among the people you’ll meet in these pages. Washington depicts lower-middle-class life in Houston as a lively, unsurprising amalgam of black, white, Asian and Latinx people. He gives us multiculturalism as naturalism. The book’s plot finds struggling gay couple Mike and Ben physically separating as Mike flies to Japan to spend time with his dying father. Simultaneously, Mike’s mother is arriving in Texas for a long-planned visit, only to discover her son is splitting and leaving her to spend several weeks with his African-American boyfriend, who she’s never met before. Continents apart, communicating through awkward text messages, Mike and Ben test the limits of their couplehood while simultaneously struggling with the awkwardness of their family relationships (Ben’s divorced but still-squabbling parents also live in Houston). Memorial is not a book of big dramatic moments, but its quietly rendered details build upon each other to form a story that feels revelatory in its mundanity.

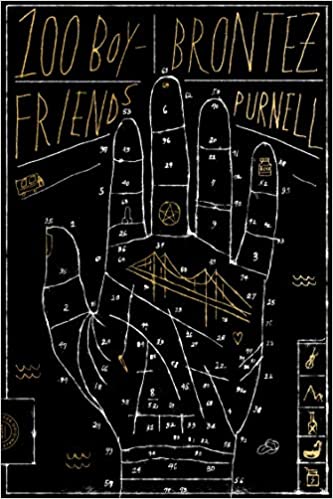

A bold, vulnerable, and thrillingly filthy piece of work, 100 Boyfriends by Oakland punk polymath Brontez Purnell (Farrar, Straus and Giroux. $15. www.brontezpurnellartjock.com) finds humane aches and genuine humor in all manner of raunchy derring-do. Sometimes you’ll belly laugh while reading it; other times you’ll wince while emitting semi-appalled snorts. In this jagged edged mosaic of autobiographical prose pieces, Purnell—who plays guitar in The Younger Lovers, toured nationally as a dancer with queer electro band Gravy Train!!!, and has written zines, children’s books, fiction and poetry—pulls no punches when it comes to sexuality, sex and race. There are thematic echoes and repeated phrases throughout the text that are worthy of careful literary exegesis, but most readers will focus primarily—and delightedly—on the book’s full-throated (among other holes) yowl of unapologetic but thoughtfully self-critical black male queerness. This is a banger of a book.