My essay on bathing culture in Iceland appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of HAMAM magazine, a gorgeous, print-only publication that is produced in Istanbul and distributed internationally at eclectic magazine stands. The pages are on such fine stock, with such beautifully colored inks that they don’t reproduce very well as scans. So below the layout version that follows, you’ll find a text only version, sans the lovely illustrations by Parisian artistCarole Maillard and the layout/design by Okay Karadayılar and Ali Taptık.

HAMAM is the dream project of Ekin Balcioglu, a native Turk, former San Franciscan and current New Mexican. I was so impressed with the magazine’s first issue last year that I reached out to her to propose this piece after returning from my residency in Iceland last summer. What a pleasure to know that one can still reach out to a likeminded and trusting soul and make a real creative connection. Thanks Ekin!

Social soaking: Iceland’s national pastime

On a late Sunday night in May 2020, more than two hundred typically aquaphilic Reykjavíkians queued up outside of Laugardaslaug, the largest of seven civic swimming facilities in Iceland’s capital city. Here and at similar gatherings all over their H20bsessed country, locals were slipping into Speedos and maillots with an intensity that might seem strange to pretty much anyone else on the planet.

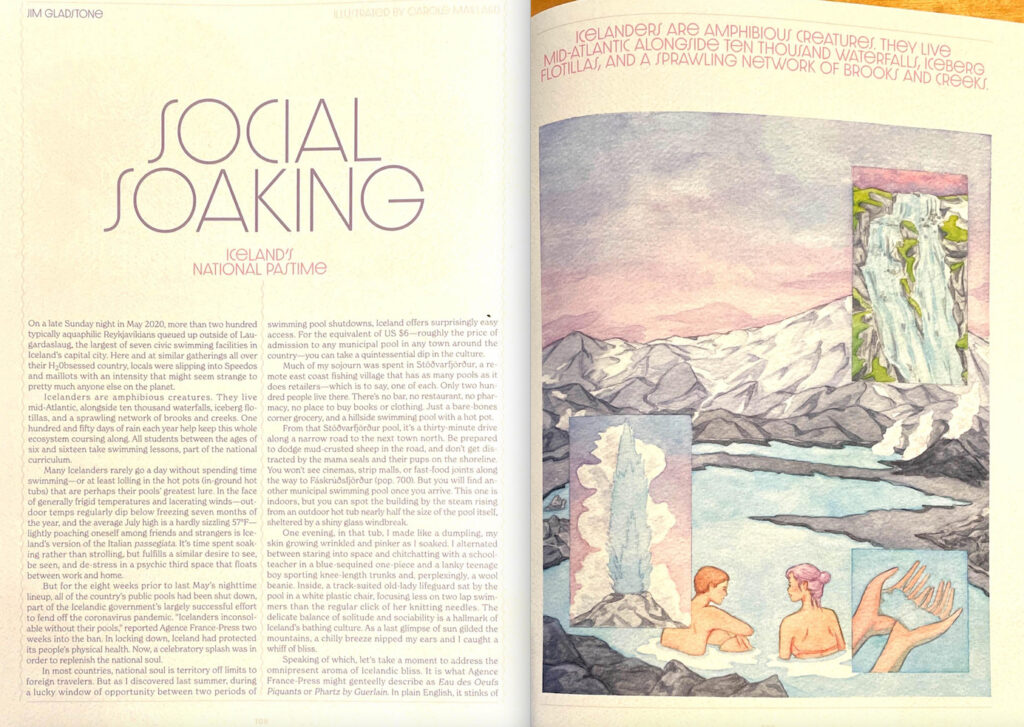

Icelanders are amphibious creatures. They live mid-Atlantic, alongside ten thousand waterfalls, iceberg flotillas, and a sprawling network of brooks and creeks. One hundred and fifty days of rain each year help keep this whole ecosystem coursing along. All students between the ages of six to sixteen take swimming lessons, part of the national curriculum.

Many Icelanders rarely go a day without spending time swimming—or at least lolling in the hot pots (in-ground hot tubs) that are perhaps their pools’ greatest lure. In the face of generally frigid temperatures and lacerating winds—outdoor temps regularly dip below freezing seven months of the year, and the average July high is a hardly sizzling 57°F—lightly poaching oneself among friends and strangers is Iceland’s version of the Italian passegiata. It’s time spent soaking rather than strolling, but fulfills a similar desire to see, be seen, and de-stress in a psychic third space that floats between work and home.

But for the eight weeks prior to last May’s night time line-up, all of the country’s public pools had been shut down, part of the Icelandic government’s largely successful effort to fend off the coronavirus pandemic. “Icelanders inconsolable without their pools,” reported Agence France-Press two weeks into the ban. In locking down, Iceland had protected its people’s physical health. Now, a celebratory splash was in order to replenish the national soul.

In most countries, national soul is territory off limits to foreign travelers. But as I discovered last summer, during a lucky window of opportunity between two periods of swimming pool shutdowns, Iceland offers surprisingly easy access. For the equivalent of US $6—roughly the price of admission to any municipal pool in any town around the country—you can take a quintessential dip in the culture.

Much of my sojourn was spent in Stöðvarfjörður, a remote east coast fishing village that has as many pools as it does retailers—which is to say, one of each. Only two hundred people live there. There’s no bar, no restaurant, no pharmacy, no place to buy books or clothing. Just a bare-bones corner grocery, and a hillside swimming pool with a hot pot.

From that Stöðvarfjörður pool, it’s just a thirty-minute drive along a narrow road to the next town north. Be prepared to dodge mud-crusted sheep in the road, and don’t get distracted by the mama seals and their pups on the shoreline. You won’t see cinemas, strip malls, or fast-food joints along the way to Fáskrúðsfjörður (pop. 700). But you will find another municipal swimming pool once you arrive. This one is indoors, but you can spot the building by the steam rising from an outdoor hot tub nearly half the size of the pool itself, sheltered by a shiny glass windbreak.

One evening, in that tub, I made like a dumpling, my skin growing wrinkled and pinker as I soaked. I alternated between staring into space and chitchatting with a schoolteacher in a blue-sequined one-piece and a lanky teenage boy sporting knee-length trunks and, perplexingly, a wool beanie. Inside, a track-suited old-lady lifeguard sat by the pool in a white plastic chair, focusing less on two lap swimmers than the regular click of her knitting needles. The delicate balance of solitude and sociability is a hallmark of Iceland’s bathing culture. As a last glimpse of sun gilded the mountains, a chilly breeze nipped my ears and I caught a whiff of bliss.

Speaking of which, let’s take a moment to address the omnipresent aroma of Icelandic bliss. It is what Agence France-Press might genteelly describe as Eau des Oeufs Piquants or Phartz by Guerlain. In plain English, it stinks of sulfur. The natives have acclimated, and over a few weeks, so did I. The warm water of Icelandic swimming pools, hot tubs, and even home showers is a product of constant subterranean friction between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates, which generates heat and sloughs minerals, most notably sulfur, into the water before it jets to the surface through natural springs, human-made boreholes, and the country’s famous geysers. The indoor and outdoor swimming pools hover naturally between 80° and 86°F, and the quick-dunk hot pots hold steady at up to 111°F.

In a country where outdoor temperatures are so frigid, it’s hard to imagine even a generous, verging-on-socialist government footing the bill to heat millions of gallons of pool volume each day. Geothermally heated water is the secret sauce of Iceland’s entire bathing culture.

****

After the restful weeks of my small-town retreat, I set out on a road trip that would incorporate some of Iceland’s more exclusive bathing experiences. While public pools charge just a nominal fee and intrepid hikers can enjoy hidden wilderness springs for free, the pricier Icelandic baths are worth visiting as well. These are by no means strictly tourist attractions; Icelanders regularly patronize more luxe options for weekend relaxation, adventures with friends, and couples’ nights out.

Genders bathe together, swimsuits are required, and Icelandic kids often accompany their parents or grandparents. So, while they are inarguably sensual environments, the baths offer little of the sexual frisson—wanted or unwanted—that one may encounter at bathing destinations in other parts of the world.

For day rates of US $25 to $60, you can spend as long as you like at these swankier baths, skipping among outdoor pools, decks, tubs, and cafés, lounges, and restaurants. They’re generally open until 9 or 10 p.m., and the evenings are magical, given the pleasurable juxtapositions of goosebump-chilly air and steaming water, gently illuminated poolscapes and jet-black, star-filled skies. Between late September and March there’s even the chance of a bathtime light show featuring the green and purple streaks of aurora borealis.

You’ll find neither Ottoman-esque opulence nor New Age spa vibrations at these privately operated escapes. But sleek Scandinavian architecture smartly harmonizes with natural surroundings, creating a sense of tranquility that contrasts quite drastically with the gymnasium atmosphere of Iceland’s civic pools, and includes the toilet and changing facilities that are missing from backcountry options.

On the outskirts of Egilsstaðir, Iceland’s third-largest city and gateway to the eastern fjords, are the Vök Baths. The complex, hidden at the bottom of a steep hillside, looks like the lair of a particularly eco-friendly James Bond villain. A pier-like wooden walkway leads to sequential polygonal soaking pools suspended in the lake and fed by lakebed hot springs. Before the springs were discovered centuries ago, local villagers attributed wintertime breakage of the lake’s frozen surface to the thrashings of an underwater monster. Today, many bathers alternate long soaks with invigorating jumps in the lake, having nothing to fear but the cold.

About 140 miles to the northwest, in the town of Húsavik, is GeoSea. Rare among geothermal baths, GeoSea’s source is an oceanic spring that fills its free-form, amoeba-shaped infinity pools with saltwater. Perched on a high cliff due south of the Arctic Circle, the pools offer panoramic views of the Atlantic and snow-covered peaks across Skjálfandi Bay. If you prefer a leviathan to a rubber ducky with your bath, bring binoculars: Húsavik is Iceland’s whale-watching capital.

One night, while soaking here, an unexpected storm threw intermittent sheets of ice-cold seawater over the pools. I hunched my shoulders, grimacing, as I tried to keep as much of my body as possible under the surface while my hair began freezing up above. Two small Russian boys on holiday with their parents laughed riotously—perhaps at me, given that their swimming gear sensibly included the same sort of woolen hat that had confounded me on that teenager in Fáskrúðsfjörður.

****

My last premium pool experience in northern Iceland was the Mývatn Nature Baths, essentially a smaller and pleasantly less-trafficked version of the country’s most popular tourist attraction. The famous Blue Lagoon pulls in tourists by the millions, in part due to its location between downtown Reykjavík and Iceland’s international airport, but Mývatn offers a similar experience in a more serene setting. Both are human-made bathing lakes with water supplied by a nearby power station. After being extracted from 1,500 feet belowground as steam to power the utility’s turbines, the water condenses and simmers down to about 100°F as it flows to the lake. At Mývatn, two waterside longhouse-style steam rooms are situated directly over geothermal vents.

The blue color and silken texture of the water are the result of natural mineral deposits, largely silica, which—in combination with the heat—are said to be therapeutic for skin conditions like psoriasis and eczema. There’s an undeniable aesthetic allure to wading in this warm, milky, azure water, but after a couple of drinks at Mývatn’s swim-up bar, I had trouble not imagining myself adrift in Smurf chowder.

When I mentioned this to Petter, a cheerful bearded bartender, he informed me that I was not so off base: There were indeed fantastic creatures nearby. Just a few miles from the baths is Dimmuborgir (loosely translated as Dark Cities), a sprawl of black lava rock formations—jagged towers, collapsing arches, hidden caves—considered in traditional folklore to be the gateway to the underworld and a dwelling place for supernatural beings. Legend has it that Dimmuborgir is home to Grýla, a vicious troll giantess who, accompanied by her thirteen savage sons, kidnaps young humans and devours their tender flesh. In past centuries, parents told tales of her rampages to their children to frighten them into staying indoors during dangerous winter weather.

In more recent times, the horror of these stories has been tamped down. Those thirteen sons have transmogrified into the mischievous but nonthreatening Yule Lads, who bring gifts to well-behaved children in the days leading up to Christmas. What hasn’t changed is the trolls’ filthy appearance and putrid stench, in part due to allegedly washing only once a year. While this monstrous baker’s dozen presumably once did their scrubbing in natural springs, they now make a sold-out annual appearance, in the form of costumed characters, at Mývatn, scouring their nasty selves as a performance for local families enjoying a holiday swim.

****

Back in Reykjavík, the day before my return home, I headed once again to Laugardaslaug, where those pool-parched Icelanders had queued for the May reopening. From the outside, the complex is modern and nondescript; inside, too, in all honesty it’s got no more architectural charm than the average US high school swim center. What’s special here is the spirit.

When Icelanders head to the water each day, they do so with a powerful sense of mutuality. In submerging, they merge. Their landscapes, their traditions and their community flow together.

“Come on in.” They welcome each other from below the surface. “The water is warm.”