One day last month, Matthew Lawrence, who is doing graduate studies in Information Science at Montreal’s McGill University, went rummaging through the clearance items at Wega Video, a 24 year old shop in the city’s gay village that is going out of business. He discovered a nostalgia-inducing treasure: Three mint condition 1990s gay porn magazines, each still sealed in a clear plastic bag to fend off sticky fingered browsers.

“I don’t know if I want to tear them open,” says Lawrence. “They’re like artifacts.”

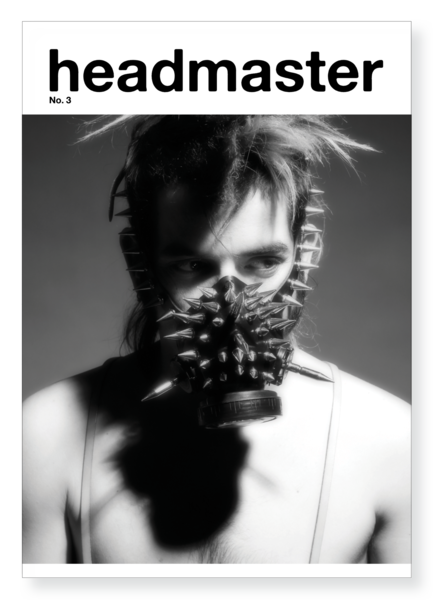

Over the past ten years, Lawrence, 40, and his partner, Jason Tranchida, 50, have been publishing Headmaster, a magazine they’ve accurately described as “a little arty and a little dirty.”

For each loosely themed issue (Field Trip, Village People, Collaboration), the Providence, RI based couple provides broadly defined “homework” assignments to gay artists and writers who use them as prompts to create pieces to be featured in the magazine.

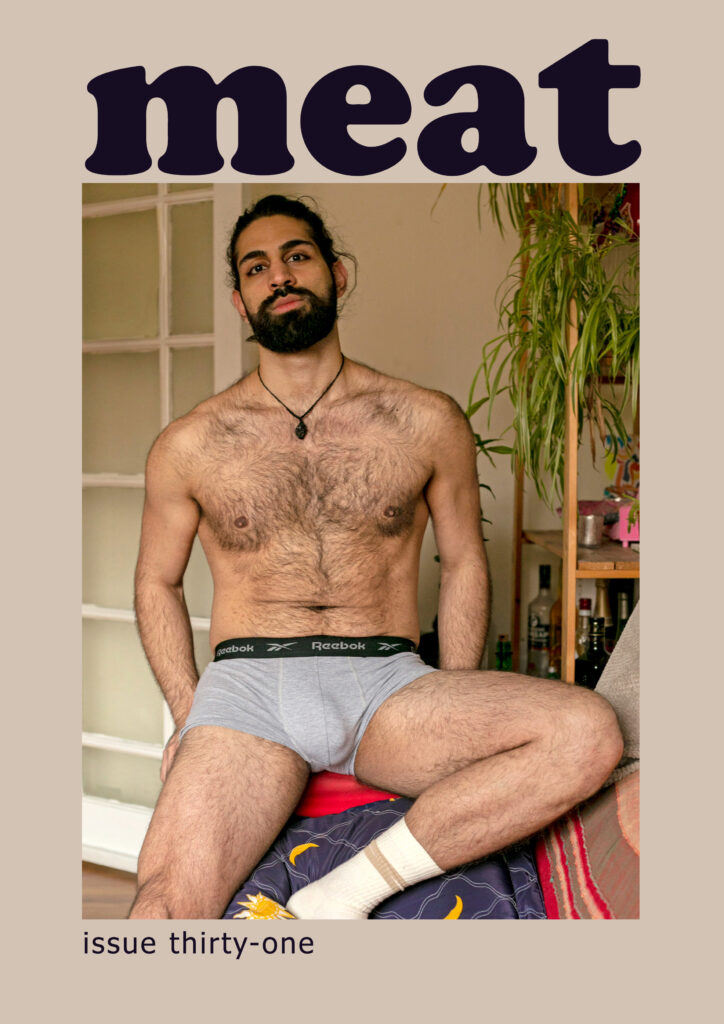

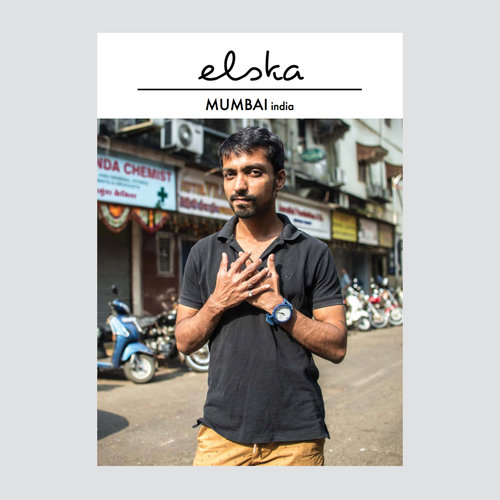

Along with other highly designed, erotically charged gay periodicals including Elska and Meat, Headmaster is staking out remarkably different ground from both internet porn and the slick printed gay ‘adult magazines’ found on newsstands from the 1970s through the first decade of our current digitized century.

“We want our magazine to be sexy,” says Tranchida, “But I can’t imagine a guy thinking ‘I wanna get off’, lemme grab my copy of Headmaster. I mean if someone super cerebral used it to get off, I’d be absolutely delighted. But I don’t think that’s happening.”

Liam Campbell, who’s been photographing and editing Elska since 2015 feels similarly. “I do sometimes get messages from people saying like oh I love this guy in whatever issue and I had a fantastic orgasm thinking about him as I read it in bed last night. But don’t think most people are using it like that.”

Each issue of Elska is shot in a different city and features photo portfolios of men—both clothed and nude—who have responded to model calls distributed through social media and word of mouth. Every subject writes a text about themselves and their city for the issue, and Campbell incorporates brief notes on his impression of each locale.

So how does Campbell, 40, imagine readers interacting with his magazine? “I hope they do what I would do if I was reading it. Maybe go to a park, sit in the grass with a cup of coffee and read it. You spend time with these people, sort of have the experience, through reading the issue, of traveling to that city, imagining you’re on a date, meeting one of these guys, having him show you around and maybe go back to his place. You should relax and take your time with it.”

While this brainier new breed of gay erotica doesn’t objectify bodies like the glossies of yore, the magazines themselves are crafted to be appreciated as objets d’art. Both Elska and Headmaster are perfect bound rather than stapled and expensively printed on luxurious stock.

“We are total paper nerds,” confides Lawrence.

To their makers and readers, these beautifully produced publications are not sources of shame to be hidden under the mattress. They are signifiers of pride, to be displayed on the coffee table.

It’s been a dozen years since the mass death of glossy gay porn magazines in the United States: The final issues of Mandate, Manscape, Men (originally published as Advocate Men), Freshmen, Playguy and Honcho all rolled off the printing presses in 2009. Over the prior decade, many other magazines had gone under as explicit gay sexual content largely migrated online where it would ultimately grow into today’s endlessly overflowing digital pornucopia.

From the late 1970s—when the loosening of postal regulations first made the mass production and national distribution of porn a viable business opportunity—until their ultimate web-driven demise, these magazines were touchstones in the lives of many queer men. In addition to being sold at gay book stores and sex shops, they could be found at a selection of urban newsstands, convenience stores, and highway rest stops. They were usually kept in the back of the magazine racks, often sealed in plastic to assure that gays paid for their predilections.

Just the act of purchasing these magazines—unlike the relatively private consumption of online porn—could feel like an act of bravery, a public acknowledgement of one’s private desires. But, in turn, the magazines helped shape those desires. Their content not only stoked sexual fantasies; it informed the nascent identities of gay men over several generations.

“There’s an input-output loop when it comes to sexual imagery and the sexual imagination,” says Gerard Koskovich, a public historian and antiquarian book dealer who has collected queer publications and ephemera for museums and university libraries worldwide.

Koskovich points out that the mass produced, nationally distributed gay porn magazines, featured pictorials with a narrow range of subjects: mostly muscular, big-dicked, white men. These images, alongside advertisements for penis enlargement, dietary supplements, and sex toys positioned as “lifestyle” products helped advance a market-driven template for how gay men should appear and what they should seek in a sex partner.

“The large scale profit-driven publishing of gay porn that began in the 1970s helped create new ideas about ‘what a dirty picture should look like’,” says Koskovich. “If an issue of a magazine featured images of a black man and didn’t sell as well as previous issues. You wouldn’t see many more pictures of black men published in that magazine.”

And when gay readers then took the magazine’s cues as to what sorts of men were sexually desirable, social prejudices were reinforced and perpetuated.

“For a short time, I worked at Attitude,” says London-based photographer Adrian Lourie, who found the British gay lifestyle magazine rather limited in its editorial vision of male beauty. “Sometimes they’d do pieces with different sorts of guys, but I felt like that was just box-ticking. Mostly of the photos were of the unattainable gym-fit studs we were all supposed to be.” “I never really saw the kind of men I fancied in gay media,” says Lourie, 50, “Punky, beary, hipster. I got a bug up my ass about it.”

And the idea of showcasing such aesthetics all together in a single publication excited him. “I made a ten page zine and put it around town. Almost immediately Gay Times wanted to write about it. There was instant buzz and there was a desire for it in the community.”

Lourie’s zine morphed into Meat, a quarterly publication he shot entirely by himself for a ten year run beginning in 2011. Currently on hiatus as Lourie focuses on promoting his recently published art book showcasing favorite images from the magazine, Meat has allowed the photographer to express his own distinctive take on masculinity rather than fueling a homogenized mass ideal.

As with Campbell’s images for Elska, Lourie’s Meat photos often feature his volunteer models in their homes. “The difference between these pictures and what you might see in old porn magazines is context. I like the photos to tell a little story about each guy. I always tell them ‘Don’t tidy up before I come.’”

“What kind of stuff does he have laying around his flat. What’s on the walls? In London, like in most big cities, people live in very small rooms with their whole lives surrounding them. The pictures can still be sexy, but its sexiness in reality, not a fantasy.”

Campbell says he thinks making Elska “has kind of solidified my values.”

“When I was in my early twenties,” he recalls. “I felt like I had a ‘type,’ But then I would spend time with someone, maybe I’d meet them at a party and we’d have this brilliant connection and all this stuff in common and suddenly I felt clearly attracted to him and wanted to just jump him.”

When he started Elska, Campbell ran with that insight, deciding to put out calls for models and work with whomever volunteered. “Being open to meeting people and getting to know them, it’s actually quite exciting for me. There are some instances where I have no idea whatsoever what they’ll look like, maybe we arrange the date and time and I have no clue. I have maybe some worries in the beginning of about how will I photograph this type of body and. And I suppose over time I just realized that I can photograph, everyone, and I can find something beautiful.”

The magazine has featured models with a broad variety of ethnicities, body types, and ages. The recent Sao Paolo issue included a transman named Bruno. “To be honest,” says Campbell recalling the photo shoot. “I had never seen a vagina in person before.”

Campbell says that over his years of publishing Elska, promoting it on his website and Instagram, and having it written about in other publications, the volunteers have grown increasingly diverse.

“It was more difficult in the beginning, convincing people that they are worthy of being photographed and presented in such a way. But my work and my portfolio has helped to convince them that ‘Yeah, I feel comfortable being part of this, because I see what you’ve done with other people who I can see some of myself in. Even though in most media I don’t see people like me, I see them in yours and I find them absolutely gorgeous.”

While Americans and Europeans seem to be growing more open to a range of looks, Campbell’s travels have demonstrated that this is not the case globally. “There still are some places in the world I go to where the standard of beauty is more crippling.”

“In Korea and in Japan, it was difficult to find people willing to take part. One guy who had planned to model he just said ‘I don’t feel attractive enough I don’t feel confident enough to do it. And I think that if people see me in this magazine, they will laugh at me.’ So, there are some places where culturally it’s still really hard.”

With small print runs of 500 to 1000 per issue, publications like Elska and Headmaster are not formulated for mass market appeal or great financial gain. The small amount of money they generate for their publisher/curators is not nearly enough to live on. Campbell, based in Queens, NY, has the good fortune of a supportive tech worker spouse. Lourie does interior design shoots for commercial magazines. Lawrence is a freelance writer. And Tranchida runs a successful design practice.

But displayed in style-setting shops, shared among savvy gay influencers and amplified by the internet, this artisan erotica showcases the eclectic tastes of both their publishers and the participants in their content; tastes that may be indicative of broader social change.

“From the 1930s to 1940s, when gay porn was very clandestine with men privately trading or selling nude photographs to one another, there was a lot of variety in the images,” says Koskovich, the historian. “Lots of body types. Different ethnicities. And you would want to keep every one of them, because you didn’t know when you would get more. You thought of what you were attracted to as ‘naked men.’ You didn’t have all these subcategories like twinks and jocks that you could pick and choose among—‘I like him and him, but not that guy’.”

“Fortunately,” says Koskovich, “I feel like we’re now on the down side of a 45-year arc in which market-driven capitalism had gained a lot of control over our sexual imaginations. Today people have so much ability to inexpensively create sexual self-representation. And I think that so many people have a desire to be seen after being erased for so long.”